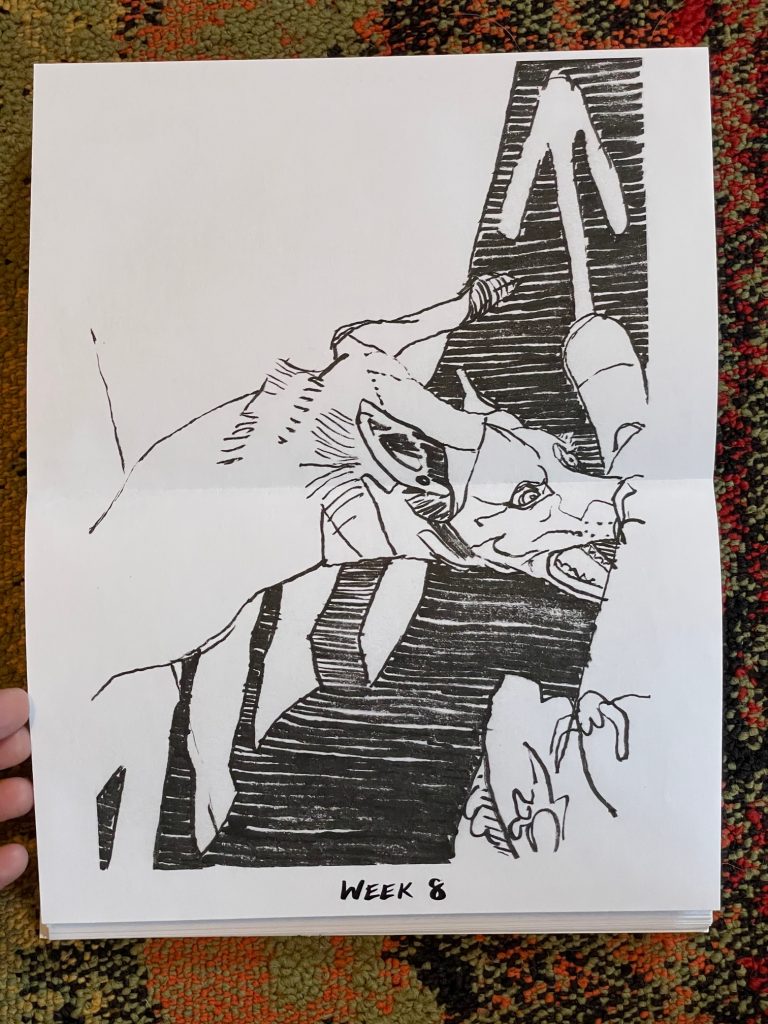

Credit: Lee Deigaard “Quarantine Drawings [March 17-May 19, 2020]”

My 18th interview in this series is with Lee Deigaard who explores the topographies where one consciousness encounters another, describing a landscape given shape and substance by its animal protagonists, their sensory and imaginative worlds and their autonomy. With language, photography/video, installation, event, and drawing, her work approaches the animal from positions of equality, collaboration, and mutual curiosity and looks at multi-species empathy, animal cognition and personality, sensory processes of memory and grief, and the nature of intimacy. As an independent artist and researcher based in urban Louisiana and rural Georgia, she has exhibited and presented her work internationally.

Credit: Lee Deigaard “Quarantine Drawings [March 17-May 19, 2020]”

LD: Inspired by Lynda Barry’s five-minute drawings of cats and her workshop Drawing and Writing the Unthinkable, I decided, somewhat arbitrarily, at the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020 to make 12 drawings each day in black ink on index cards of E dog, my companion in quarantine. The series ultimately continued for nine weeks marking primary quarantine or phase 1 in New Orleans and became 600 drawings, made from office supplies, that fit within a shoebox.

I thought of the drawings as a practice (and demonstration) of love and devotion towards E dog. Proximity to her, to ponder her quicksilver reflexes, curiosity, and intelligence is always a privilege. To know another deeply, is both granular and cosmically mysterious.

We found ways to slink around peripheries, to enter natural spaces within city parks, she climbed trees; we denned at home, I worked from bed as she slept with her head on my foot. The headlines found their way into the drawings. Walking with her and drawing her were essential solaces. Both derived from companionship; both relied on daily practice and commitment which is the foundation of love, and, incidentally, of art-making.

I follow her lead. She leads me.

EM: What are your thoughts on walking as artistic practice?

LD: Walking is the medium and the message. It enacts states of porousness that yield insights. Walking is not conclusive but immersive, translatory. It transubstantiates. Walking is thinking like drawing. E dog has shown me how walking and its traces, footprints, scents, is history and future folded within. We are part of these topographical “drawings” of ephemeral presences.

As with the practice of the flaneur, to walk without destination is most revelatory. Sometimes schedules dictate, and we must walk for duration of discovery instead.

Walking in woods, as many have said (“forest-bathing”) is meditative. Moving while thinking is a meditation guided by topography, structures organic and man-made, and other lives and presences.

The outdoors are my studio. Therefore, walking is my thinking and processing. It is ruminative. It is mechanical. It can be perseverative. It is hard for one’s brain to let go and be. Therefore, it is good for the body to carry the brain through different terrains.

Walking is receptive more than transmissory. It is deep listening; the imagination and the somatic body link themselves. Phytokines from trees play a role as does exertion on mountains and hills yielding endorphins conducive to play and other inspirations.

Making a drawing of a tree (as one example) I find myself “listening” for rhythms which are entirely visual. I know that to walk as I need to walk, I must have all my senses alert. E dog shares her amplified senses with me, and we become a pair, a duality, our conversation with each other as we walk is physical and nonverbal, but it is also explicit. Her total receptivity and keenness informs mine.

She conducts a visual conversation with me using her body (and secondarily, the lines of the leash) to underline and express fleeting alignments and discoveries within urban (but also natural) spaces. I take photographs, shot from the hip as it were, cued by her pauses and interactions. How she moves, and how I move relative to her reveal angles of discovery and an essential and consciously rendered geometry.

Walking is a way to be suspended in the sensory world, to cope with uncertainty, to hold in the mind’s eye the beauty of companionship and the venturing forth as a pairing.

Walking embodies what writing sentences followed by other sentences into paragraphs, into texts, is. Or what a pencil upon the page finds, roving. All of these are paths from within the imagination (its own forest).

Walking, like blind contour drawings, is the line, the mind, finding the terrain. The imagination is terrain, too. We, like the deer, groove paths (often trenches).

Walking is unadorned. It’s devotional. It’s motivated and unmotivated. It enacts a thread, a moving through an immensity, which is always the world.

Credit: Lee Diegaard, “1941/AIDA” -Across the Creek, Aida and her calf, photograph through artist’s window

EM: Can you tell us about any recent or upcoming projects you are excited about?

LD: A recent and ongoing project 1941/AIDA looks closely in tribute and inspiration at an escapee cow who leaves home a number and returns a name. It is a story of becoming through assertion of self and will and making bold decisions in moments of fear. I walk to trace her movements, to better understand her decisions, to know the ground beneath her feet. The project consists of forensic cyanotypes, drawings exploring her amplifying facial expressions, sculptural installations, poetry, presentations, collaborations, and the ensuing networks of imagination and empathy her story grows and creates among her witnesses primary, secondary, and tertiary. I ask myself the question, in art, in life: What would AIDA do?