New zine! If you’re Minneapolis, you can pick one up for free from a selection of Free Little Libraries on Colfax Ave S, or you can order online. Check out Edible Weeds for the map and the product link.

by Ellen Mueller on July 20, 2024, no comments

New zine! If you’re Minneapolis, you can pick one up for free from a selection of Free Little Libraries on Colfax Ave S, or you can order online. Check out Edible Weeds for the map and the product link.

by Ellen Mueller on July 7, 2024, no comments

New zine! If you’re Minneapolis, you can pick one up for free from a selection of Free Little Libraries on Bryant Ave S, or you can order online. Check out Edible Weeds for the map and the product link.

by Ellen Mueller on June 22, 2024, no comments

I’m working on some new compositions in a body of work I’ve titled, Rewilding. I’ve posted a selection of the pieces on a new gallery page. Check it out and share widely!

by Ellen Mueller on May 25, 2024, no comments

Image Credit: Annie Dugan

UPDATE: we had to cancel this event due to an unforeseen conflict. We will work on rescheduling. Thank you!

I hope you’ll join me on Sunday, June 9, 2024 at 1pm for a free Walking Artist Talk with Cecilia Ramon and myself. We’ll be gathering at Free Range Film Barn near Duluth, 909 County Road 4 Wrenshall, MN 55797

I’ll talk a little about my recently released book, Walking as Artistic Practice, which features one of Cecilia Ramon’s walking works! Cecilia will also be leading a walk, and there is a labyrinth we’ll explore at Free Range Film Barn. Plus, there will be a limited number of FREE copies of my zine, “Walking Workbook: Labyrinths and Mazes” – first come, first served! Come learn more about walking as artistic practice, and enjoy Q&A at the end.

by Ellen Mueller on March 17, 2024, no comments

Documentation image of “Teatro del Sole / Theater of the Sun” David Allen Burns and Austin Young / Fallen Fruit, commissioned by Manifesta 12, 2018. The artwork is the hand drawn map of approximately 500 sites in the ancient city of Palermo where seasonal fruit, street art, and religious altars exist in public space. The wallcovering is created from hundreds of photographs of fruits and flowers that we found while mapping the public right of way in the ancient city.

As part of the release of my book, Walking as Artistic Practice (orders now open for softcover! Discount code: XNIP424), I’m going to be publishing some brief interviews with the various artists, authors, researchers, creatives, collectives, and platforms whose art practice, written material, or other works I cite and mention.

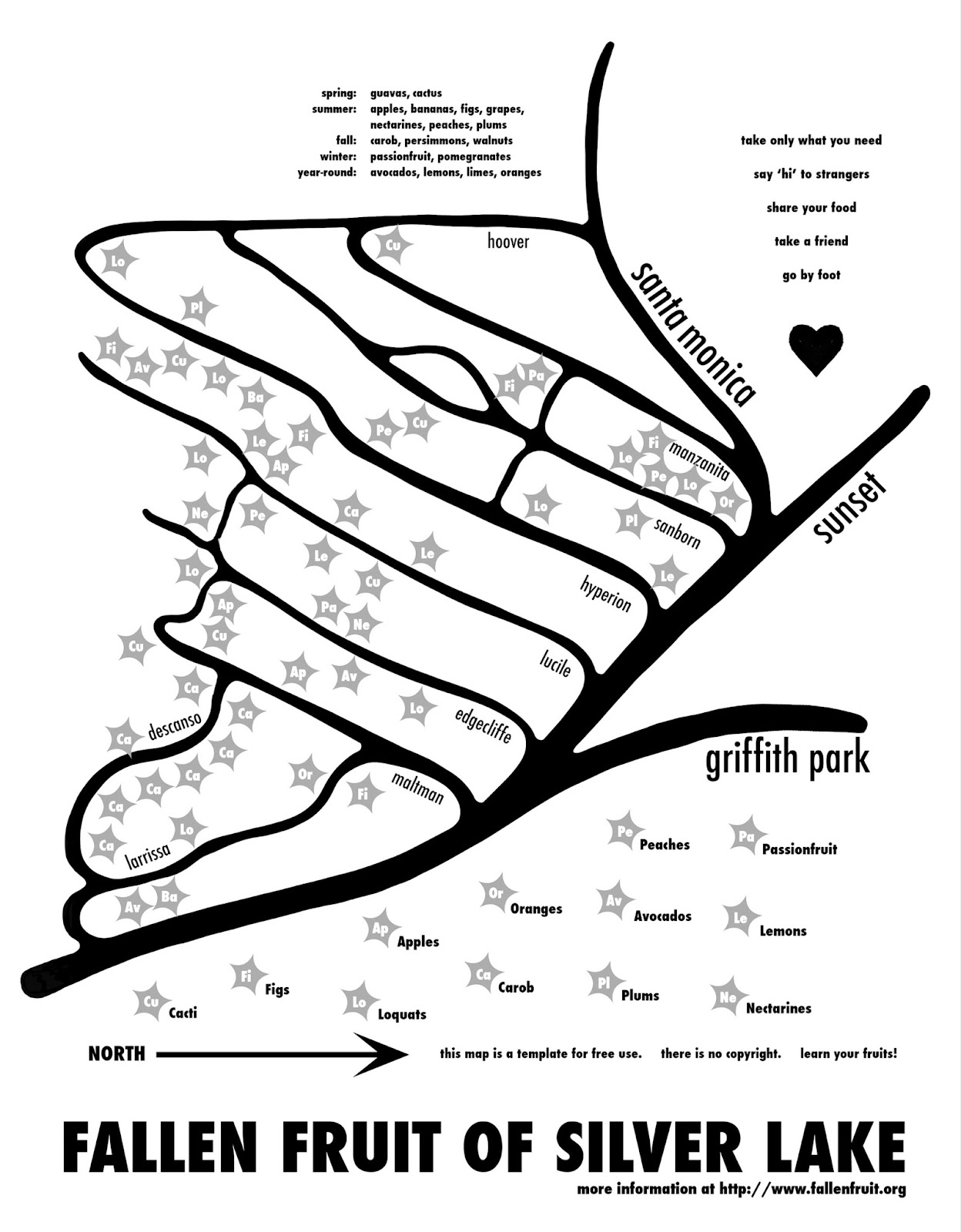

My 27th interview in this series is with Fallen Fruit, which is an art collaboration originally conceived in 2004 by David Burns, Matias Viegener and Austin Young. Since 2013, David and Austin have continued the collaborative work. Fallen Fruit began in Los Angeles with creating maps of public fruit: the fruit trees growing on or over public property. The work of Fallen Fruit includes photographic portraits, experimental documentary videos, and exhibition projects. Using fruit (and public spaces and public archives) as a material for interrogating the familiar, Fallen Fruit investigates urban space, ideas of neighborhood, and new forms of citizenship. From protests to proposals for new urban shared spaces, Fallen Fruit’s work aims to reconfigure the relationship of sharing and explore understandings of public and private. We learned that “fruit” can be many things; it’s a subject and object at the same time it is aesthetic. Much of this work is linked to ideas of place and family, and echoes a sense of connectedness with something very primal – our capacity to share the world with others.

The Fallen Fruit Map of Silver Lake, a neighborhood in Los Angeles, 2004. David Allen Burns, Matias Viegener, and Austin Young / Fallen Fruit

EM: First, thank you for chatting with me about Fallen Fruit’s work Public Fruit Maps (2004-). I cite this project in chapter two (Analyzing Walking Works) in the subsection on “Maps and Mapping.” How would you describe the project for people who might not be familiar with it?

FF: It’s important to see this artwork, the collection of Public Fruit Maps, in a historical context. We started this project in 2004 in Los Angeles and the project began as a response to a call for projects by the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest. The prompt for submissions asked to explore the impulses of activism (doing the right thing) but without opposition — not against anything. We wrote a manifesto called ‘Fallen Fruit’ that declared that cities should plant fruit trees to share in public spaces and we made a hand drawn map of the fruit trees we found in the margins of public space in Silverlake, our neighborhood. We asked the question: ‘If a branch of a fruit tree hung over the sidewalk, but the trunk was on private property – who owned that fruit on that branch. And who has the right to use public spaces?”

We discovered from research that there are no federal, state, or county laws about the use of fruit in “public spaces.” Instead it is up to cities to create these laws and they are not all the same. In Los Angeles, we learned that when a branch hangs over a fence then it is in the “public realm.” That makes it “public domain,” and something that is sharable by anyone passing by. It is important to learn what the laws state in whatever city you are located.

At that time in Los Angeles there were a lot of artists interested in new ideas about creating art that was not made for walls in a gallery but that existed in the social interactions created by a shared activity. It was also a time before the ‘green movement’ or urban farming. We began giving walking tours of our map in Silverlake. It was huge. People were excited about the idea of picking fruit in public space.

Documentation image of a Fallen Fruit nocturnal fruit forage with the public in Los Angeles, circa 2008.

EM: What are your thoughts on walking as artistic practice?

FF: Fallen Fruit were creating walking maps – we made the first one of Silverlake in Los Angeles in 2004., and then everywhere we were invited. We understood that we were invoking something experienced based that was both subjective and objective at the same time, and also referenced a long history of action artworks, group dynamics, and the use of the idea of what we call ‘public.’ We thought there was nothing more important than getting off your cell phone, getting out of your car, walking your neighborhood, saying hi to strangers, meeting your neighbors. In those days after 2005-2006 – we were included in group exhibitions with other artists, like Amy Franchescini, The LA Urban Rangers, and Fritz Haeg, creating works that involved walking and contemporary art exhibitions like ‘Civic Matters’ at LACE and “Fair Exchange’ at the LA fairgrounds both curated by Irene Tsatsos and at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, ‘The Gatherers’ co-curated by Berin Golonu and Veronica Wiman in 2008. and Machine Project’s Field Guide to LACMA’, curated by Mark Allen in 2008. (https://www.academia.edu/6021007/Exhibition_brochure_for_The_Gatherers_Greening_Our_Urban_Spheres_co_curated_by_Berin_Golonu_Yerba_Buena_Center_for_the_Arts_2008 )

Documentation image of planting fruit trees for our artwork, ‘Monument to Sharing,’ in neighborhoods surrounding Los Angeles State Historic park in 2015.

EM: Can you tell us about any upcoming or recent projects you are excited about?

FF: We are coming up on our 20th year of making art as a collaborative project called Fallen Fruit. We are living artists with a living art practice. Our artwork is in constant response to our daily lives. One thing we are really excited about is that we have been awarded a fellowship with the Nevada Museum of Art for 2023 / 2024. They are supporting us to collect 20 years of our archive that will be available in their research library. It’s been an incredible process to look back at our practice. We just installed another ‘Monument to Sharing’ as a permanent artwork surrounding the museum property in Reno. We completed an epic permanent artwork at the 21c Museum Hotel in St Louis ‘The Way Out West’ and we installed a permanent work in Rome, Italy, called ‘Trappola d’Amore / Love Trap’ at Chiostro del Bramante. And in Bergamo, Italy at the Accademia Carrara called, ‘Sacred Conversations.’ We were just invited to the Karachi Biennale and we’ll be making a project with The Parrish in the Hamptons, New York.

The Fallen Fruit Map of Palmero, David Allen Burns and Austin Young / Fallen Fruit, Sicily, Italy, 2018. This map includes locations of fruit bearing plants along the ancient alleys, streets, parks, and staircases. Locations include street art and religious altars both of which are important to the landscape along the boundaries of public and private space in Palermo.